Trending

Father of Two Tragically Electrocuted on High-Tension Pole in Bayelsa

Published

7 months agoon

By

Ekwutos Blog

A father of two, identified as Amas, tragically lost his life on Friday after being electrocuted on a high-tension pole near the Ekeki Police Station on Azikoro Road in Yenagoa, the Bayelsa State capital. Amas, who was not an employee of the Power Holding Company of Nigeria (PHCN), was attempting to connect clients to the federal power line when the fatal incident occurred.

Due to the poor power supply in the state, residents prefer the federal line, which provides 12-13 hours of stable power daily. Amas, originally from Nembe Local Government Area, was reportedly stuck on the pole for hours before PHCN officials arrived to retrieve his body.

An eyewitness, Michael Orubo, lamented the loss, saying, “Amas lives on our street and handles most of the connection work in this area. Why has death come to him in such a way? He just left us playing a chess game and said he would be back, but he never returned.”

Another eyewitness recounted, “He passed me not more than five minutes after the rain stopped. The next thing I heard was people screaming. We rushed to the scene but couldn’t help because he was strapped tightly to the pole and it was still raining.”

It took hours for PHCN officials to arrive and bring down Amas’s lifeless body. His mother, who has a shop nearby, was devastated and couldn’t bring herself to see his body. The community is now consoling her as they mourn the loss of Amas, who was described as easygoing and a devoted father.

Follow Ekwutosblog for more………….

You may like

Jigawa governor loses mother, son within 24 hours

Dramatic Blaze Engulfs Funke Akindele’s Luxury Mansion in Intense Film Shoot

Nigerian Songstress Waje Claps Back at Troll Who Mocked Her Age

Nollywood Star Tobi Bakre Gets Heartfelt Tattoo of His Children’s Faces

Max takes the Box Office by storm, scores highest opening of 2024

Faith Kipyegon: 3 Times Olympic Winner Excites Kenyans with Ugali Cooking Skills on Christmas Dayj

Trending

Dramatic Blaze Engulfs Funke Akindele’s Luxury Mansion in Intense Film Shoot

Published

2 hours agoon

December 26, 2024By

Ekwutos Blog

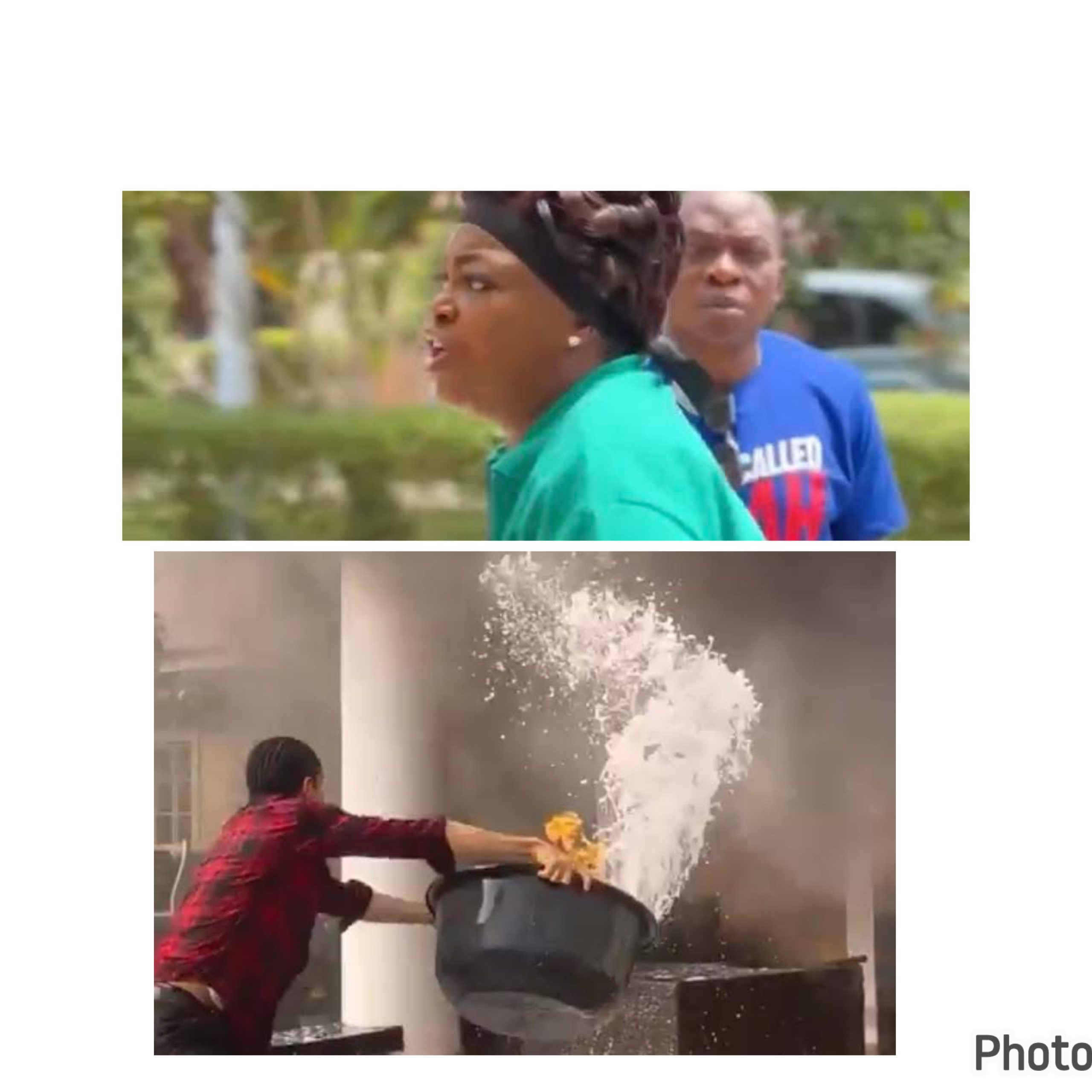

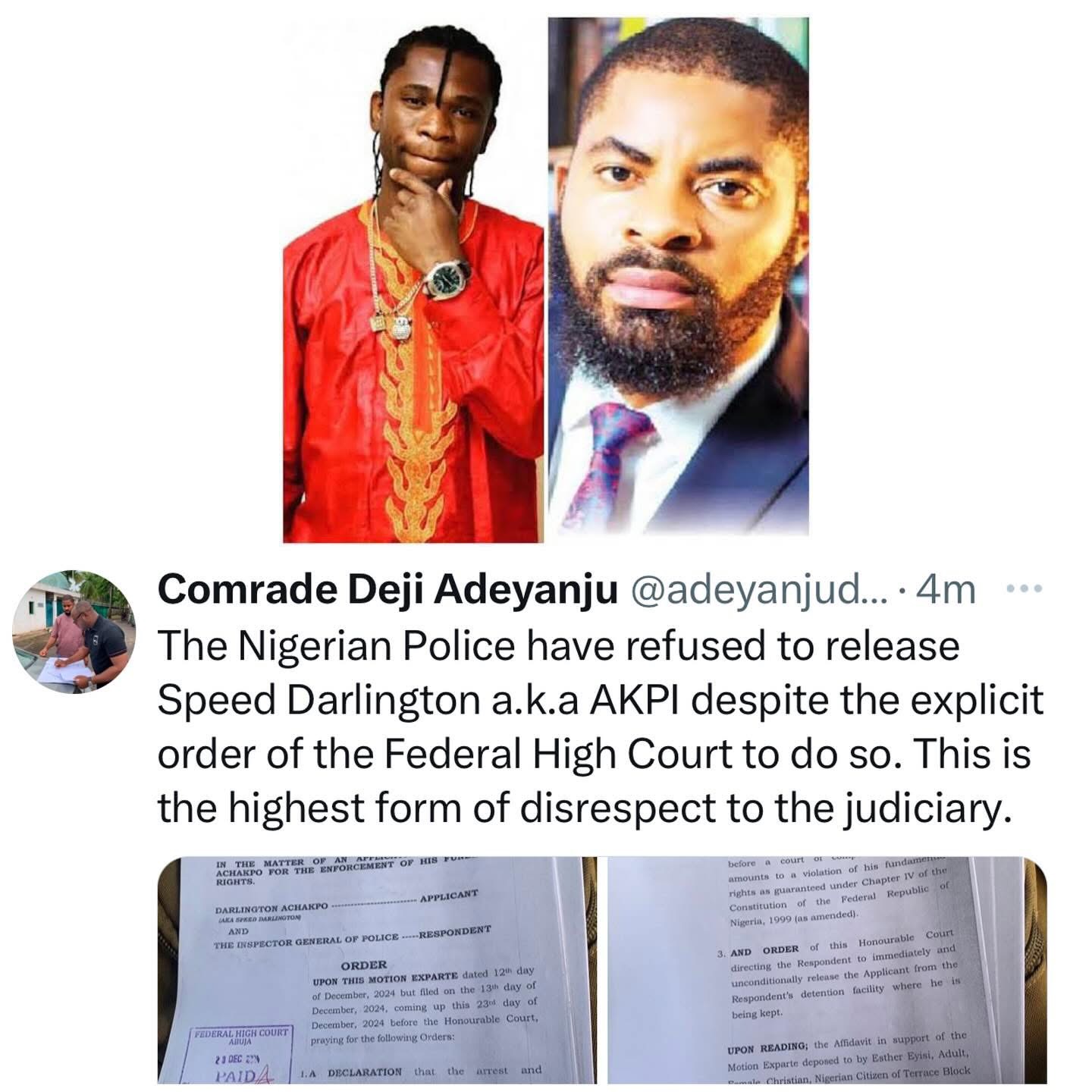

A heart-stopping behind-the-scenes video from Funke Akindele’s forthcoming movie, Everybody Loves Jenifa, has ignited intense buzz online. The captivating clip shows a meticulously staged inferno sweeping through her opulent residence during filming, prompting the cast and crew to scramble for safety.

What’s striking is Akindele’s composed demeanor amidst the seeming chaos, underscoring her meticulous planning and attention to detail. Insiders reveal that the fiery scene was carefully choreographed in tandem with the Lagos State Fire Service, ensuring a delicate balance between cinematic authenticity and safety.

Jubril Giwa, Senior Special Assistant on New Media to the Lagos State Governor, publicly commended Akindele’s strict adherence to safety protocols via a post on X.

Photo source: X

Trending

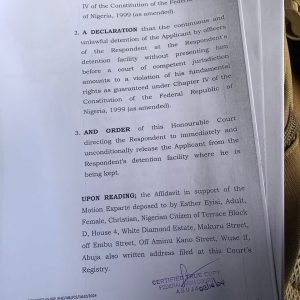

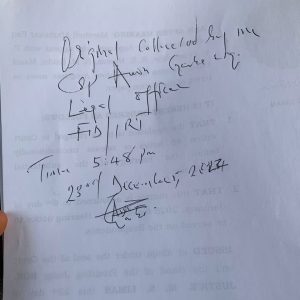

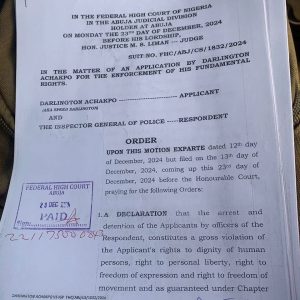

The Nigerian Police have refused to release Speed Darlington a.k.a AKPI despite the explicit order of the Federal High Court to do so- Deji Adeyanju

Published

13 hours agoon

December 26, 2024By

Ekwutos Blog

The Nigerian Police have refused to release Speed Darlington a.k.a AKPI despite the explicit order of the Federal High Court to do so- Deji Adeyanju

Trending

What happened to Britain’s Ukrainians? Refugees tell their stories

Published

13 hours agoon

December 26, 2024By

Ekwutos Blog

Three years after moving from her native Kharkiv to forge a new path in the Ukrainian capital of Kyiv, Yana Smaglo was doing nicely.

A gifted businesswoman with an insatiable work ethic, she had her own fashion and beauty operation, a nice apartment and an office in the city centre. Life was good.

‘It was settled, nice, a comfortable life,’ says Yana, who is now 32. ‘I was very happy.’

On 24 February 2022, shortly after 5am, everything changed. Yana awoke to the sound of explosions; the long foreshadowed war with Vladimir Putin‘s Russia had begun.

She hurriedly called her friends to waken them. One planned to drive west, towards the border with Poland, and invited her to come along.

In an instant, Yana’s survival instinct kicked in. She grabbed a hat, stuffed a few belongings into a small rucksack – documents, cash, a laptop – and rushed from her home.

In the most literal sense, she was closing the door on life as she knew it.

‘When I left my apartment I thought that, probably, I would never see it again,’ says Yana, before pausing to add ruefully: ‘I also lost the business.

Ukrainian fashion designer Yana Smaglo was forced to leave everything behind when the war with Russia began, but has rebuilt her life in the UK after receiving a visa

Yana has established her own fashion business in the UK, which has five brands in its portfolio, more than 120 wholesale partners and, Smaglo says, a £120,000 turnover

Yana poses in one of her Ukrainian-made designer coats at Almscliffe Crag, near Harrogate, Yorkshire. ‘Local people really helped me as I was trying to grow the business,’ she says

‘It’s hard to explain to yourself that, no, you don’t have anything any more, you need to buy, you need to work hard,’ says Yana Smaglo. ‘It’s hard emotionally’

‘But at that moment, you’re so shocked and scared, you think only about saving yourself. I understood that to save myself physically, I didn’t need anything.’

Yana is nonetheless a born entrepreneur and, even in extremis, her natural enterprise did not desert her. Snatching a few handbags, she stuffed them in her backpack, realising she could sell them if she needed ‘quick money’.

That resourcefulness would serve her well once she had made her way across Poland and Germany to Strasbourg, where, after a short wait, she was granted a UK visa.

Almost 6.2 million Ukrainian refugees have fled across Europe since the Russian invasion began, with the UK among a cluster of major host countries that includes Germany, Poland and the Czech Republic.

Those who sought sanctuary in Britain were able to take advantage of government initiatives enabling Ukrainians already in the country to extend their visas, and for family members to join them.

There was also a sponsorship programme, Homes for Ukraine, under which UK householders received a monthly payment of £350 – rising to £500 after the first year – in return for hosting refugees.

Statistically speaking, these various schemes were a notable success. Research conducted by the University of Oxford’s Migration Observatory suggests the number of Ukrainians living in the UK has quadrupled since the conflict began, rising from 41,000 in 2021 to roughly 160,000 by this summer.

In February, the government announced that Ukrainians initially granted three years to remain in the UK would be able to apply for an 18-month visa extension, ensuring Britain remained ‘a safe haven for those fleeing the conflict’.

Alina Bulakh, who helped to manage the Ukrainian Olympic team at London 2012, is one of 23 people hosted under the Homes for Ukraine scheme by James Baird, a West Sussex farmer

Following her arrival on Baird’s farm in Climping, West Sussex, Kharkiv-born Alina initially found work in a nearby pub in Arundel

After joining a dating app, Alina found a match in Edinburgh, where she is now living with her partner and his two children from a previous marriage

But for many of the roughly 212,000 people who have arrived under the schemes (some of whom have since returned to Ukraine or moved on elsewhere), resettling in the UK has been a case of out of the frying pan and into the fire.

James Baird, a farmer from West Sussex who has hosted 23 people under the Homes for Ukraine scheme, says the knowledge that there is a potential end date to their residency makes it difficult for refugees to put down roots.

‘There is no new life, because they’re in a space of adjusting to being in limbo,’ says Baird. ‘They can’t get on with their lives here and they can’t get on with life at home, so that’s brought about a tremendous number of issues.’

Not least among those is the psychological toll, with anxiety about the future compounding the impact of displacement, the trauma of experiencing the war at first hand, and concern about loved ones still in Ukraine.

‘Refugees abroad face not only material challenges but also profound psychological difficulties that impact their ability to rebuild their lives,’ UN Global Compact Ukraine, which provides free mental health support to people affected by the war, said in a statement.

‘The struggles faced by displaced persons and refugees often remain invisible to society, but have a devastating impact on their lives.’

That impact includes myriad practical challenges, ranging from the language barrier and cultural differences to finding jobs, securing school places and registering for bank accounts, GPs and dentists.

‘When somebody arrives, you’ve got to build this temporary life for them,’ says Baird. ‘I found myself doing things I’ve never done before, like going to the job centre and helping people get bus passes and national insurance numbers.’

Ukrainian refugees are seen weeding the crops on Baird’s farm. Valeriia, in the foreground, is from Odessa; at work behind her is Vitalli, who is from the Lviv Oblast

James Baird, second from left, poses with Andriy Ohinok and family. Ohinok, a businessman from Lviv, has worked closely with Baird’s charity work in Ukraine

James Baird, left, with his friend Simon Ulrich, after donating a truck filled with aid supplies to the armed forces of Ukraine special forces unit, as part of the Pickups for Peace scheme

Baird has also offered less conventional forms of assistance.

One of the first Ukrainians he hosted was Alina Bulakh, a woman in her early 30s from Kharkiv who had previously helped to manage the Ukrainian Olympic team. Though she quickly found work in a pub in nearby Arundel, it was a far cry from her previous visit to the UK for the 2012 London Olympics.

‘It was a wonderful and interesting time, we worked and equipped the Olympians for the Summer Olympics in London 2012 and the Winter Olympics in Sochi 2014,’ says Alina.

She found it difficult to adjust to her altered circumstances, so when she informed Baird that she wanted to join a dating app, he helped her to navigate the sign-up process.

When she subsequently mentioned wanting to visit Edinburgh, he sensed a further opportunity to lift her spirits, using some of the money he received as a host to cover her travel arrangements.

‘What I didn’t realise was that she had messaged a guy on Tinder,’ Baird recalls. ‘She met up with him in Edinburgh, and love blossomed. She’s now living with him; he’s a divorcee with a couple of kids, and she’s like a mother to those children, so it was really wonderful.’

Not everyone is so fortunate.

Natalia, a 27-year-old from Donetsk, fled to the UK after the outbreak of war but was afflicted by crippling fear and anxiety. She has since returned home – albeit to a different part of the country – where she has received support from UN Global Compact Ukraine’s mental health platform, helping her to deal with her traumatic experiences.

Natalia, who says she went went back to Ukraine to pursue her business interests and regain a sense of normalcy, laid bare the inner turmoil of life as a refugee.

‘Fear was constant,’ she said. ‘It consumes your entire body, leaving you restless day and night. When survival becomes your only goal, everything else loses meaning – your job, your plans, even your sense of self.

‘You leave everything you’ve known and move to another country. There, you take on any job you can find, even if you were a specialist before. And again, you feel torn apart: you’re living in safety, but part of your soul remains at home, where everything is destroyed.

‘When you return, you have to start all over again, but it’s even harder, because you carry the pain of your past with you.’

When Ira Lisova, 19, was seven months pregnant, she was struggling financially and feared she would have to send her baby to an orphanage. Baird offered her support and Artem, now five months old, remains safely with his mother

Baird, left, is seen with Ulrich, centre, and members of the Ukrainian Special Operations Forces after delivering a truck filled with aid supplies as part of the Pickups for Peace initiative

The psychological burden is almost invariably compounded by practical obstacles. Baird says the people he has hosted have all been ‘fiercely independent’, but he has seen firsthand how self-reliance can be complicated by factors beyond their control.

‘Even when they enter the mainstream economy, they are often professional people who are washing dishes in pubs and picking cabbages around the outskirts of Chichester, he says. ‘So they’re on a very low wage, but very well educated.

‘It’s really difficult, because the landlord-tenant system here requires personal guarantees that you have some sort of cash security,’ he says. ‘I’ve stepped in as guarantor quite a few times, but then they’ve got to find work – and they have to have enough work to pay the rent and pay all the bills.’

Even that may not be enough, as Yana Smaglo can attest.

Within two days of arriving at Manchester Airport, from where she travelled to west Yorkshire to stay with friends, Smaglo was seeking employment.

When the initial signs were unpromising, she changed tack, drawing on her industry experience to establish Nenya Fashion, a Leeds-based company that sells a distinctive range of Ukrainian lines.

Two years on, the results speak for themselves: the business has five brands in its portfolio, more than 120 wholesale partners, and had a turnover of over £120,000 last year, says Smaglo.

Despite turning a profit, however, she has found it difficult to find alternative accommodation following the recent expiry of a one-year tenancy agreement, with landlords wary of letting to a self-employed refugee.

‘It’s quite stressful,’ says Smaglo, who once again finds herself living with friends. ‘I rented my previous accommodation for one year and I was never late with my payments.

‘I’m earning the money to pay for a room but, just because I’m a refugee and people don’t trust that a refugee can set up a business and afford to pay rent, I’m really struggling to find a place to live.’

It is the latest in a series of head-spinning events for the entrepreneur, who initially found it hard to reconcile her past and present.

‘It wasn’t easy, it was hard to understand,’ she says. ‘For example, when I rented accommodation, I wondered why I should buy something that I already have at home.

‘It’s hard to explain to yourself that, no, you don’t have anything any more, you need to buy, you need to work hard. It’s hard emotionally.

‘You can’t put all these thoughts together in your head. You’re shocked, because you worked all your life so hard, and for so long, and some people just came and took it from you in one day.

‘Physically you’ve been saved, but mentally you’re trying to understand what’s happening. I had a lot of panic attacks when I arrived here.

‘You’re in a new country, with a new language, and you start your life from zero. Your mental health starts to fray.’

Her success in coming to terms with the sea change in her circumstances was underpinned by several factors. She had the drive and business nous to help herself. She speaks good English, having learned the language in school from the age of six (although she says that coming to the UK made her feel she didn’t understand English at all).

Like so many successful entrepreneurs, she also had a little help along the way, with friends, local businesses and even the local media helping her to make the contacts she needed to get her company off the ground.

‘Local people really helped me as I was trying to grow the business,’ says Smaglo, who runs the concern with the support of two people who help pro bono with their knowledge and connections.

‘From my side, I’m here, I’m paying taxes here, I have my business here, I feel myself as a part of society. I don’t have any benefits, and I don’t want them; I’m living here now, and I want to feel the country as the rest of the British people.’

The long-term goal now is to grow the company to the point where she can not only help businesses in her homeland survive, but also employ Ukrainian refugees in the UK.

‘A lot of Ukrainians are refugees now, but it doesn’t matter where we are, we still have to help our country to survive and go through this war,’ says Yana. ‘It won’t be forever, but as long as it’s going on we need to help, to show ourselves that we are still Ukrainians.

‘It doesn’t matter where we live, we are all helping: some people are going to the frontline economically, and they should do everything they can so that less people die on the frontline.’

Earlier this year, President Volodymyr Zelensky remarked that ‘the unity of Ukrainians spans both hemispheres of the Earth’, the exodus from the country having created a global community that ‘have not forgotten their roots and do not let the world forget about Ukraine’.

Yana is part of that community – and like so many, she is intent on doing her bit.

Jigawa governor loses mother, son within 24 hours

Dramatic Blaze Engulfs Funke Akindele’s Luxury Mansion in Intense Film Shoot

Nigerian Songstress Waje Claps Back at Troll Who Mocked Her Age

Trending

- Politics10 months ago

Nigerian Senate passes Bill seeking the establishment of the South East Development Commission.

Business11 months ago

Business11 months agoInflation hits record high of 29.90% on naira weakness

Politics7 months ago

Politics7 months agoBREAKING: Federal Gov’t Offers To Pay Above N60,000, Reaches Agreement With Labour

SportsNews10 months ago

SportsNews10 months agoOlympic Qualifiers 2024: CAF Confirms Dates For Super Falcons Vs Banyana Banyana

Politics10 months ago

Politics10 months agoGovernor Hope Uzodinma’s New Cabinet In Imo: The Gainers, The Losers

- Entertainment10 months ago

American Singer Beyonce makes history as first Black woman to top country chart

Politics7 months ago

Politics7 months agoBREAKING: Organized Labour suspends strike for one week.

- Business10 months ago

Reasons we cannot sell cement below N7,000, by Dangote, Bua, Lafarge